Mitigating the growing shortage of nurses would clearly start with addressing the challenges in the training sector as quickly as possible. (Photo: Misha Jordaan / Gallo Images via Getty Images)

Almost half of the nursing workforce in SA is set to retire in the next 15 years. This suggests existing shortages of nurses will become even greater unless we take concrete steps to boost nurse training and retention.

Nurses make up a large part of the healthcare workforce in South Africa, but almost half of them are set to retire in the next 15 years, making current shortages only the start of what is likely to be a growing problem.

National spokesperson for the Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa (Denosa), Sibongiseni Delihlazo says, “This is a ticking time-bomb that is just waiting to blow up in the face of South Africans.”

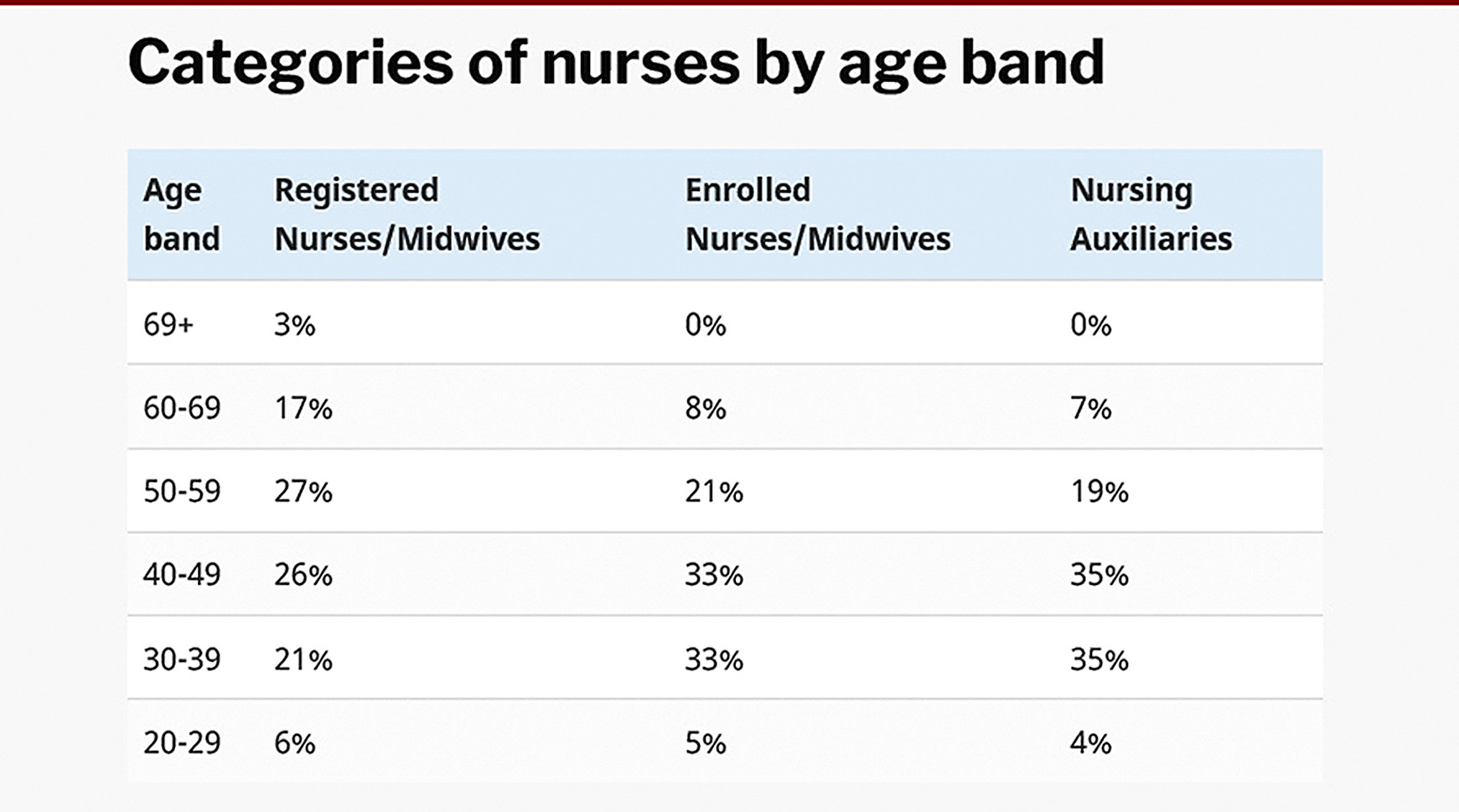

According to 2020 statistics from the South African Nursing Council (SANC), the current age demographics of registered nurses and midwives are heavily skewed towards older practitioners, with less than a third under the age of 40. The statistics show 27% of registered nurses are in their 50s, 26% in their 40s, and only 21% in their 30s (see table for more detail).

The demographics of enrolled nurses and nursing auxiliaries are only slightly more evenly distributed.

The set retirement age for nurses in the public sector is 65, although some extensions are allowed. This means, in short, that in 15 years, 47% of registered nurses will have retired. The same applies to about 26 to 30% of the enrolled nurses and nursing auxiliaries.

‘We have a crisis’

“We have a crisis of an ageing workforce,” says Prof Laetitia Rispel, the South African Research Chair on the Health Workforce at Wits University. She explains that while this is an international problem, South Africa’s relatively young population makes this worrying.

“It’s not just the replacement of the actual individuals, but you also have to look at the cumulative experience and wisdom in the health system, and that’s not going to be replaced unless we sort of take action now,” she says.

The Rural Health Advocacy Project has been doing a variety of consultations with stakeholders in the nursing field in the past months. Project officer in their human resources for health programme, Lungile Gamede, explains that while there is no exact data available on how this compares across the nation, “we have no doubt that communities living in rural areas will bear the brunt with the severe shortages that will be exacerbated when almost half of the registered nurses and midwives retire round about the same time”.

According to South Africa’s 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy, if nothing substantial is done, it is projected that by 2025, only four years away, there will likely be a shortage of about 34,000 registered nurses in primary healthcare.

Historical causes

The current and anticipated future shortages seem to come down to overall systemic issues as well as particular shifts in nursing. “It’s an underinvestment in human resources for health in general and a historical neglect of nurses and nursing,” says Rispel.

Prof Helen Schneider from the School of Public Health at the University of the Western Cape explains that there has been an “increasing professionalisation of nursing with longer, more expensive training, with growth of expectations in status and remuneration”. She says this has created issues of supply and affordability, and growing divisions of labour at the base of the system.

Funding of staff contributes strongly, according to Delihlazo.

“Firstly, poor HR planning and continuous reduction of budgets for funding nursing education by government are at the core of the problem,” he says.

According to the president of the Young Nurses Indaba, Lerato Mthunzi, working conditions add to the problem, making the nursing profession less attractive. She says because of burnout and the “brain drain”, many have left the profession or the country for better working conditions abroad, putting pressure on those who remain. She says general wards now have ratios of about 20 to 30 patients to one nurse and assistant, as opposed to the norm of around five to one, shifting the focus from quality care to just managing.

Gamede explains that this crisis will have a negative effect on the ability to provide primary healthcare, given the important role of nurses in this, as well as undermine the health system’s ability to focus on TB and HIV care. Key health indicators, especially of children, and the general ability to reach the health-related Sustainable Development Goals will be compromised.

Issues with training

According to statistics published on the SANC website, the total number of nurses on their register has increased from around 238,000 in 2011 to around 280,000 in 2020. This amounts to an increase of 18%, roughly in proportion with population growth over the same period.

These numbers seem to indicate that South Africa has made little or no progress over the past decade in addressing its nursing shortages. Furthermore, recent setbacks in nurse training may mean that shortages will get worse before they get better.

In 2020, legislation changed to require all nursing education institutions (NEI) to register as higher education institutions (HEI), which was previously only linked by university nursing departments. The CEO of the Nursing Education Association, Dr Nelouise Geyer, explains that this “should improve the critical-analytical skills of graduates” but that the transition has created a significant gap in the number of graduates.

She explains that many smaller private schools have closed down because they could not afford to register as an HEI. Public nursing colleges did not meet the requirements, although the Minister of Higher Education created a transitional arrangement to let them qualify temporarily.

Geyer says, “The most challenging change is that only universities have been accredited to offer the professional nurse programme – this will result in an almost 80% drop in the production of professional nurses in three years’ time.”

Geyer is particularly concerned about the shortage of specialist nurses, none of whom have been trained during 2020 and 2021 due to none of the specialist programmes having been newly accredited. She is not hopeful that many will resume next year.

The national health department confirms that there are currently 17 universities accredited as well as 10 public and 10 private nursing colleges. The total number of students that can be admitted for training per year per programme is around 5,900.

Mthunzi says she heard that those taking the new accredited courses report having a lot of problems with it. She says the lecturers also feel unsupported and frustrated, often lacking the right qualifications, “which leaves them really behind in terms of being more effective or enabled to deliver content as required”.

Changing course

A response from the health department on these issues indicated that their focus in these matters is on “developing nursing education and practice nationally to cope with the demands and ensure alignment to nursing workforce planning”.

Mitigating the growing shortage of nurses would clearly start with addressing the challenges in the training sector as quickly as possible. Schneider says the new curriculum needs to be correctly implemented urgently, while Delihlazo says we should “reopen the previously closed nursing colleges as of yesterday” and increase training infrastructure.

Gamede explains that change could come in urgently accrediting more training institutions in the form of strengthening the Community Services Programme, improving poor working and living conditions and adjusting remuneration. Gamede says to help equip nurses better, training should be more accessible and less centralised, with nursing education institutions being held more accountable.

Beyond the tricky business of training more nurses, effective steps towards realising the Human Resources of Health Strategy are crucial. On paper it looks strong and includes a focus on digital health technology, “the harmonisation of accreditation, registration, and regulation of NEIs” and to “institutionalise functional governance structures with empowered, competent, accountable and capacitated nurse/midwife leaders and managers at national, provincial and district levels”.

Rispel, who was involved in the strategy writing process, says that unfortunately, little has been implemented, but that the starting point would be understanding what resources there are and need to be, and working towards this.

“One of the key recommendations made was that there was a need for a highly specialised human resource intelligence and information system, that should be set up in the national Department of Health, and that would be able to develop credible planning models that would be able to collect information that we’ll be able to forecast and also highlight what are the policy levers that should be utilised,” she says.

While there are various models that are already outlined in the strategy, it is clear that change would start with implementation. Rispel says, “In our strategy, we certainly highlighted that, regardless of which modelling you use, we will require an additional number of health workers.”

While SANC did respond to media requests from Spotlight, they mostly shared statistics and did not provide substantive comment on other issues. DM/MC

This article was produced by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest.

![]()

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3j218Tl

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment